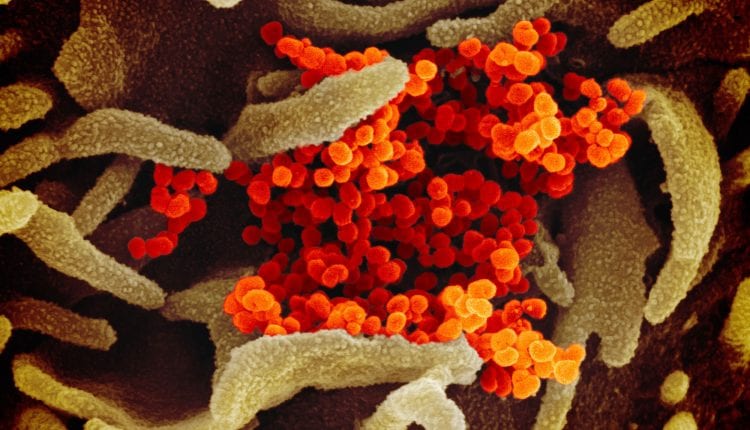

Studies in Sweden suggest that T-cells, not antibodies, could hold the clues to fighting off coronavirus.

The body should show two types of immune response to viral infection; producing both antibodies, which prevent the virus from invading the system, and T-cells, which tell infected cells to destroy themselves to prevent the virus from spreading.

But the studies in Sweden showed that many coronavirus patients were producing T-cells, but no antibodies.

Most research into coronavirus immunity assume that if an infected person produces antibodies, these will give a degree of protection against further infection. This may wear off over time, and it hasn’t been long enough for anyone to establish just how much if any long-term protection antibodies will give against re-infection.

See also: Coronavirus: Is It Safe to Re-open Schools in September?

Since vaccination relies on the antibody system to work, if antibodies aren’t being produced in some coronavirus patients, it throws into question the whole vaccination approach to fighting the infection.

See also: Aberdeen In Local Lockdown After Coronavirus Clusters

Special times

“I don’t know another virus like this,” says Rory de Vries, a virologist at the Erasmus Medical Center in the Netherlands. “We are living in special times with a special virus.”

The body’s first line of defence is the immune system, which fights off infection by raising the body temperature (causing fever symptoms) and attempting to poison the invading cells.

See also: Could Malaria Drugs Help Fight Coronavirus?

If this fails, antibodies bind to a virus in an attempt to stop it entering the body’s cells, and killer T-cells look for virus-infected cells and tell them to self-destruct in a process known as apoptosis.

When their job is done, the level of antibodies and T-cells declines so that they don’t clog up the system. But a low level of each remains so that if the same pathogen invades the system again, it can be recognised. Theoretically a person infected for a second time could show no symptoms.

The level of antibodies in the blood can be measured easily in a blood test, so epidemiologists tend to concentrate on measuring this level to get an idea of the level in infection. But T-cells are harder to detect, requiring a complex process of separation and protein testing to assess their levels.

See also: How Can Dietary Supplements Build a Better You?

New direction

Daniela Weiskopf, an immunologist at the La Jolla Institute for Immunology in California, says “It’s just not practical to test for T cell response in large samples.” But when studies started showing patients who showed T-cell levels but no antibodies, it led to new direction for research.

In fact immunologist Adrian Hayday at King’s College London says that a treatment approach using T-cells may be a viable alternative to the conventional immunisation approach. “It kind of looks like T cells could be really useful to you in this infection,” he says, citing several new papers on SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses as proof.\

See also: Do Traditional Cures For Insomnia Really Work?

Studies in Berlin found that 83 percent of COVID-19 patients produced helper-T cells, a cousin of the killer variety, which stimulate antibody production. Researchers suspect that these helper-T cells were produced in response to other infections such as the common cold (which is also a form of coronavirus).

In fact the German researchers think that this may be why some people infected with COVID-19 show no symptoms – they may have an existing level of partial immunity. This could be good news if it implies that T-cells respond to a wide range of viruses, and may still function even if the virus mutates.

See also: Chronic Pain Syndrome Should Not Be Treated With Painkillers Says NICE Report

Levels of protection

Of course, the question still remains what levels of protection from infection T-cells can provide, or how long it might last. Your pre-existing T-cells responses may well have an effect on how much protection you get from a vaccine.

It’s a new direction for research, but the conclusion is uncertain. Immunologist Daniela Weiskopf says “We’ve been dealing with this virus for six months, so we cannot know about what might happen 12 months out.”

If the studies in Sweden suggesting that T-cells, not antibodies, could hold the clues to fighting off coronavirus are correct, we may need to look in a whole new way at an approach to fighting off the pandemic.